Isn’t everything up on the internet for free? Yes, most new books and articles appear in digital format, but NO-O-O they’re not (yet) mostly free. Libraries pay big bucks to license them, and the licenses require libraries to restrict access to narrow audiences (students, faculty, or people physically inside the library).

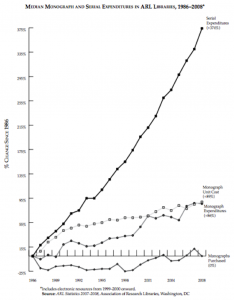

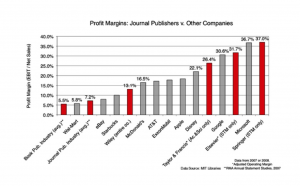

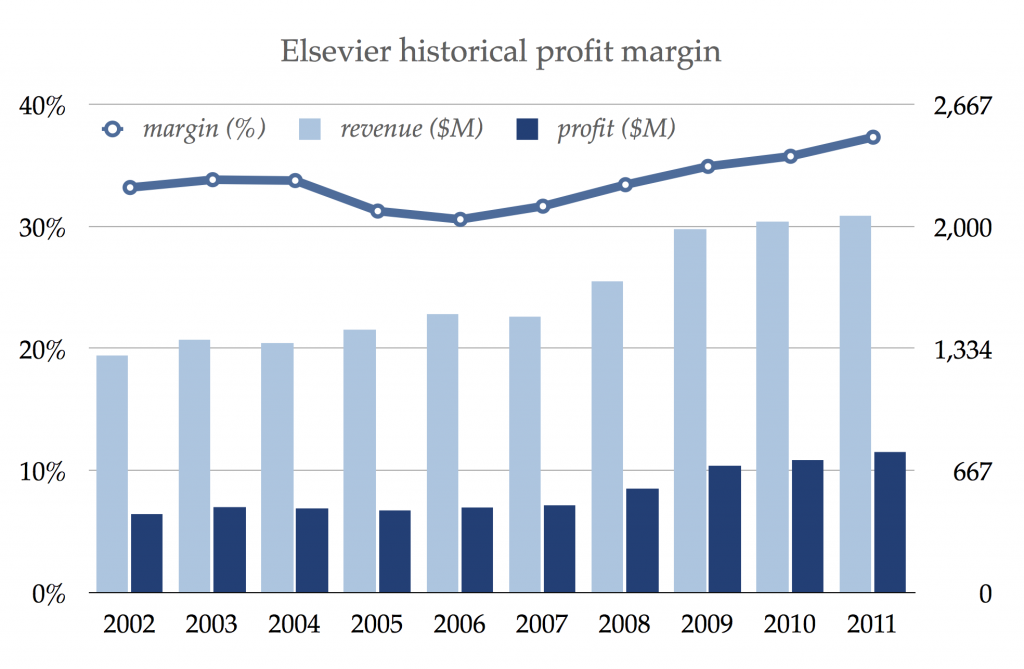

- Publishers sell journal articles for $15, $20, $35 or more, but people affiliated with a licensing library get them for free. U.S. copyright law enables restricted access and constructs a formidable barrier to information for anyone without a university affiliation. Some publishers profit mightily from this arrangement. Elsevier, Springer, and Wiley all routinely clear around 30% profit by selling journal articles back to universities through library expenditures.

Elsevier clears more profit than Walmart, Apple, and Disney. Data are from Mike Taylor, The obscene profits of commercial scholarly publishers, 2012. Chart by Stuart Shieber, 2013.

- U.S. copyright law as applied in traditional scholarly publishing protects publishers interests at the expense of readers and authors.

- Online digital display of most post-1923 American book titles is limited to a few pages, unless you buy a licensed copy yourself or access it through your library license.

- Challenging U.S. copyright law and scholarly publication practices, activist Aaron Swartz drew a civil lawsuit for downloading a ton of JSTOR articles using a computer stashed inside a MIT’s library IP-space. (See Lawrence Lessig’s video about Swartz’s copyright activism).

The required readings for the Graduate Center’s Spring 2013 JustPublics365 POOC are selected not only because they’re interesting and relevant, but also because they’re available in a free and open digital format. Lots of what we want to read is still locked up behind digital pay walls; we were only able to liberate some of it. For this course, many of the suggested readings are marked with an asterisk. This means that to reach them online, you have to be a Graduate Center affiliate (with an active GC network userid/pwd) or an affiliate with another subscribing institution.

The Open Access (OA) movement seeks to change this. OA advocates ask writers, particularly academics who give their work to publishers for free, to publish open access with a Creative Commons license so readers everywhere can at least read/view it for free, then re-use and re-mix according to the author’s rules. Scholars want the widest possible impact by reaching the widest possible audience. Librarians want to stop spending insane amounts of money to publishers for academic work the university has already subsidized with faculty salaries. Readers want to read for free.

Academic authors and activists have to make it happen. Publish in a journal that is all (or “gold”) open access with DOAJ.org. Or use a SPARC sample contract to negotiate with your publisher to retain author copyright. Or, use the Sherpa/Romeo tool to find a journal’s standing permission for open access author archiving (“green” open access). About 95% of academic journals have standing permission for authors to post already-published articles on the web after a 6 – 24 month embargo. If every academic would post their articles following publisher guidelines already in place, there would be lots more reading available for our Spring 2013 POOC.

A few academic book publishers experiment with open access, but there are relatively few new open access books. Books published in the USA prior to 1923 may be in public domain (unless publishers extend copyright protection), but post-1923 US books can’t be distributed on the web without tempting copyright litigation. Nearly all the books available free online are so old that the copyright protections have expired, or, they’re government works-for- hire, or, the authors subscribe to the principle that academic work should be free to the public. Posting anything online from a copyright-protected book, even a single PDF book chapter password-protected for “reserve” reading by traditional university course, can tempt litigation.

A team of CUNY faculty, students, and librarians select and review every reading for this course. We’ve done our best to point you to the finest open access reading available, but we wish we had more to choose from. It’s up to all of us to transform the academy, to support open access scholarly publishing, and to make the work of public higher education a greater force for the common good.